Samuel R. Delany’s science fiction novel Empire Star introduces an intriguing trio of concepts: simplex, complex and multiplex. They concern how much a mind is stuck in one world view or how much it can think through multiple ones. Unfortunately, the concepts as “explained” — and more often exemplified — in the novel are left very obscure. I first ran into them in books by the scientists Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen, but reading the original novel almost made me more confused about them. Yet, I have found the concepts as best I’ve been able to understand them to be useful for describing at least one thing: why and how people see contradictions where there really are none, or don’t see how points of view can be reconciled when they can.

I looked on the internet for an analysis of the concept trio, but didn’t find much of one. I did find a collection of quotes from Empire Star, which is included below. I don’t yet feel up to writing an analysis simply saying what the concepts mean, but I thought it would be helpful to create a bigger collection of quotes about them — including from Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen, who may or may not have understood them as the original novel intended, but in any case make use of some version of the concepts. They both explain them more clearly than the original and give additional examples of their application. Some other authors have also said relevant things and will be mentioned here.

So: If you want to go straight to the clearest definition, click here to see one by Cohen and Stewart. If you want to start with quotes from the original work, click here or just scroll down a bit.

I am using the concepts myself in another article, which also provides examples of how to apply them, though I won’t copy the text in this article. I recommend seeing this other article as well, though: “A synthesis of religious belief and naturalism?”

Index

Empire Star (Samuel R. Delany)

Figments of Reality (Stewart & Cohen)

A note on Zarathustrans (Stewart & Cohen)

The Science of Discworld (Stewart & Cohen)

Less Wrong: “Introducing Simplexity” (“ArisKatsaris”)

Book Riot: “Simplex, Complex, Multiplex: Samuel R. Delany and Experience vs. Reading” (James Wallace Harris) (Will add link when I figure out how to do it in the new WordPress setup.)

Thinking in Systems (Donella H. Meadows)

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal: “Clouds 2” (will add link)

I’ll probably add something more here in the future.

Empire Star

Thanks to the compiler of the collection at http://www.autodidactproject.org/quote/delaney2.html; most of this is just copied from there to save me having to retype them.

I have a multiplex consciousness, which means I see things from different points of view.

[p. 6]

“Perhaps I can explain it in purely metaphorical terms, though painfully I know that thou wilt not understand until thou hast seen for thyself. Stop and look above.”

They paused in the broken stone and looked up.

“See the holes?” she asked.

In the plating that floored the bridge, here and there were pinpricks of light.

“They just look like random dots, do they not?”

He nodded.

“That’s the simplex view. Now start walking and keep looking.”

Comet started to walk, steadily, staring upward. The dots of light winked out, and here and there others appeared, then winked out again, and more, or perhaps the original ones, returned.

“There’s a superstructure of girders above the bridge that gets in the way of some of the holes and keeps thee from perceiving all at once. But thou art now receiving the complex view, for thou art aware that there is more than what is seen from any one spot. Now, start to run, and keep thy head up.”

Jo began to run along the rocks. The rate of flickering increased, and suddenly he realized that the holes were in a pattern, six-pointed stars crossed by diagonals of seven holes each. It was only with the flickering coming so fast that the entire pattern could be perceived–

He stumbled, and skidded onto his hands and knees.

“Didst thou see the pattern?”

“Eh . . . yeah.” Jo shook his head. His palms stung through the gloves, and one knee was raw.

“That was the multiplex view.”

[pp. 16-17]

“You’re not noplex,” the Lump said. “Your view of things is quite complex by now—though there is a good deal of understandable nostalgia for your old simplex perceptions. Sometimes you try to support them just for the sake of argument.

…

“Lump, I don’t think you do understand. So listen. Here you are, in touch with all the libraries and museums of this arm of the galaxy. You’ve got lots of friends, people like San Severina and the other people who’re always stopping by to see you. You write books, make music, paint pictures. Do you think you could be happy in a little one-product culture where there was nothing to do on Saturday night except get drunk, with just one teletheater, and no library, where maybe four people had been to the university, and you never saw them anyway because they were making too much money, and everybody knew everybody else’s business?

“No.”

“. . . . You couldn’t be happy there, I could. It’s as simple as that, and I don’t really think you fully comprehend that.”

“I do,” Lump said. “I hope you can be happy in someplace like that. Because that’s what most of the universe is composed of. You’re slated to spend a great deal of time in places like that, and if you couldn’t appreciate them, it would be rather sad.”

[pp. 48-50]

“The multiplex universe doesn’t appeal to me. I don’t like it. I want to get away from it. If I’m complex now, it’s too bad, it’s a mistake, and if I ever get back to Rhys, I’ll try as hard as I can to be simplex. I really will.”

“What’s got into you?”

“I just don’t like the people. I think it’s that simple. You ever heard of the Geodetic Survey Station?”

“Certainly have. You run into them?”

“Yeah.”

“That is unfortunate. Well, there are certain sad things in the multiplex universe that must be dealt with. And one of the things is simplexity.”

“Simplexity?” Jo asked. “What do you mean?”

“And you better be thankful that you have acquired as much multiplexity of vision as you have, or you never would have gotten away from them alive. I’ve heard tell of other simplex creatures encountering them. They don’t come back.”

“They’re simplex?”

“Good god, yes. Couldn’t you tell?”

“But they’re compiling all that information. And the place they live—it’s beautiful. They couldn’t be stupid and have built that.”

“First of all, most of the Geodetic Survey Station was built by Lll. Second of all, as I have said many times before, intelligence and plexity do not necessarily go together.”

“But how was I supposed to know?”

“I suppose it won’t hurt to outline the symptoms. Did they ask you a single question?”

“No.”

“That’s the first sign, though not conclusive. Did they judge you correctly, as you could tell from their statements about you?”

“No. They thought I was looking for a job.”

“Which implies that they should have asked questions. A multiplex consciousness always asks questions when it has to.”

“I remember,” Jo said … “when Charona was trying to explain it to me, she asked me what was the most important thing there was. If I asked them that, I know what they would have said: their blasted dictionary, or encyclopedia, or whatever it is.”

“Very good. Anyone who can give a non-relative answer to that question is simplex.”

“I said jhup,” Jo recalled wistfully.

“They’re in the process of cataloging all the knowledge in the Universe.”

“That’s more important than Jhup, I suppose, ” Jo said.

“From a complex point of view, perhaps. But from a multiplex view, they’re about the same. First of all, it’s a rather difficult task. When last I heard, they were already up to the B’s, and I’m sure they don’t have a thing on Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaavdqx.”

“What’s . . . well, what you just said?”

“It’s the name for a rather involved set of deterministic moral evaluations taken through a relativistic view of the dynamic moment. I was studying it some years aback.”

“I wasn’t familiar with the term.”

“I just made it up. But what it stands for is quite real, and well worth an article. I don’t think they could even comprehend it. But from now on, I shall refer to it as Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaavdqx, and there are two of us who know the word now, so it’s valid.”

“I guess I get the point.”

“Besides, cataloging all knowledge, even all available knowledge, while admirable, is . . . well, the only word is simplex.”

“Why?”

“One can learn all one needs to know; or one can learn what one wants to know. But to need to learn all one wants to know, which is what the Geodetic Survey Station is doing, even falls apart semantically. . . .”

[pp. 59-61]

This next part comes after a weird and frankly not as such believable scene where the protagonist Comet Jo encounters a poet who seems to have experienced everything he has, even literally involving the same place and people.

“The thing you were saying about multiplexity and understanding points of view. He completely took over my point of view, and you were right; it was uncanny.”

“It takes a multiplex consciousness to perceive the multiplexity of another consciousness, you know.”

“I can see why,” Jo said. “He was using all his experiences to understand mine. It made me feel funny.”

“You know he wrote those poems before he even knew you existed.”

“That’s right. But that just makes it stranger.”

“I’m afraid,” Lump said, “you’ve set up your syllogism backwards. You were using your experiences to understand him.”

“I was?”

“You’ve had a lot of experiences recently. Order them multiplexually and they will be much clearer.” And when they are clear enough, enough confusion will remain so that you ask the proper questions.”

[pp. 73-74]

“You’ve got to make allowances. When people become as militant as he is, the most multiplex minds get downright linear. But his heart’s in the right place. Actually, he said a great deal to you if you can view it multiplexually.”

[p. 78]

“There are certain walls that multiplexity cannot scale. Occasionally it can blow them up, but it is very difficult, and leaves scars in the earth. And admitting their impermeability is the first step in their destruction. . .”

[p. 80]

“Then I want you to take a complex statement with you that is further in need of multiplex evaluation: The only important elements in any society are the artistic and the criminal, because they alone, by questioning the society’s values, can force it to change.”

[p. 84]

SOURCE: Delany, Samuel R. Empire Star. New York: Ace Books, Inc., 1966.

Figments of Reality

(This passage gives the most comprehensive and relatively clearest definition for the terms that I’ve seen.)

A multicultural world will require new kinds of thinking. In 1966 the science fiction writer Samuel R. Delany published a little-known but highly unusual novel called Empire Star. The main narrative is a convoluted time-travel/many worlds story which eats its own tail. It concerns the (rumoured) freeing of the Lll, a race of creatures whose architectural abilities are so immense that they have become slaves, so desperately needed throughout the galactic empire that they cannot be permitted to be free. But the philosophical subtheme is a remarkable study of how human minds structure their vision of the universe. ‘Simplex, complex, multiplex’ is a running catch-phrase.

The test for a simplex mind is to ask it what is the most important thing in the universe. If it answers, then it is simplex — be it a mind on the backwoods satellite Rhys, which knows that the most important thing in the universe is its staple crop, plyasil, or the incredibly sophisticated technoculture writing the Encyclopaedia of Everything, which is similarly focused on a single overriding goal.

A complex mind can perceive the many intertwining strands of cause and effect that combine, within some consistent worldview, to constrain and control the unfolding of a particular selection of events. Complexity is a state that is inaccessible to the vast proportion of the human race, but as the global village shrinks, more of us take the complex view.

Rarer still is the multiplex mind, which can work simultaneously with several conflicting paradigms. It sees not just one interpretation of reality, but many, yet it sees them as a seamless whole. Such a mind is untroubled by mere inconsistency: it is comfortable with a mutable, adaptive, loosely coherent flux. The real universe (inasmuch as there is one), says Delany, is multiplex. Order your perceptions multiplexually, and you will understand the universe on its own terms.

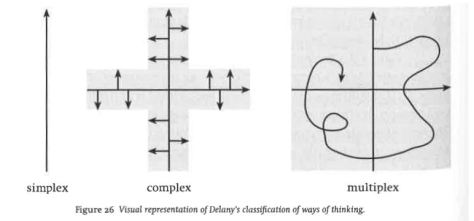

In The Broken God another SF writer, David Zindell, added a fourth type of mind: omniplex, embracing the Cosmic All. But Delany would have denied that there was a Cosmic All to embrace, as do we — because the concept of omniplexity is a simplex thought. A very big simplex thought, but simplex for all that. Figure 26 [scanned below] illustrates Delany’s three ways of thinking. A simplex mind wanders along a single, fixed axis. A complex one explores the region around several axes, by making small excursions away from one axis in the direction of the other(s). A multiplex mind explores the uncharted territory between the axes, making unexpected connections. Complexity produces explorations, multiplexity produces explosions.

[pp. 289–290]

(Continuing right after the above, an application to describing cultures.)

There was a time when human cultures were simplex. Tribes living in small villages or travelling in hunter-gatherer clans shared a single vision of their place in the world. However, the simplex, tribal mind cannot deal with external realities that go outside its limited experience. The tribal snooker break [metaphor for system that keeps itself going] continues because all tribal authority rests on the priests, but when the priests do not know what to do … typically they do the wrong thing, and disaster follows.

The barbarian approach is equally ineffectual. Operating by social rules such as ‘honour’, ‘glory’, ‘prowess’, ‘vengeance’ — figments that have not evolved complicitly with the outside world and therefore fail any stringent reality-check — falls apart because it cannot mount a coherent response to a substantial new threat.

A note on Zarathustrans (Stewart & Cohen)

In both their book The Collapse of Chaos and the previously mentioned Figments of Reality, Cohen and Stewart sometimes illustrate some of their points with stories about the fictional aliens called the Zarathustrans. In Collapse, human space travellers encounter Zarathustrans on their own planet, whereas in Figments, Zarathustrans observe the Earth. They look vaguely like flightless birds, but this resemblance is superficial, and they’re both very alien and very human at the same time. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about them is that they have evolved not to be entirely independent individuals but to live in groups of eight Zarathustrans (plus one symbiote of a different kind). This means not only that they are obsessed with the number eight and see numerological significance based on it everywhere, but also that they naturally think in a multiplexual way and find simplex thinking hard.

Humans are naturally simplex and have a harder time becoming complex or multiplex. The difference to Zarathustrans is illustrated by a comment from one of them:

“Their thought patterns intrigue me. I have been trying to make sense of their way of thinking. They appear to — well, I was going to say ‘place the universe in a different phase space’, but that is not how they think. The closest image I can fin in humanspeak is that they carve up the universe differently from us. A curious way to smell things. … What I mean is, they seem to think of the world in terms of fixed things instead of fluxy processes. And the way they understand things is to carve them up[.] … It appears complementary to our way of thinking, rather than opposed.”

(Figments of Reality, pp. 181–182. Emphasis added.)

What is most puzzling about this is that the Zarathustrans seem very limited in their own way. In some sense, they are definitely having problems rising above what I’d call simplexity in some sense. For one thing, like I said, they are obsessed with the number eight in a way that seems entirely contingent on their own evolutionary history. This is evidently clever commentary on how we and the things we regard as obvious would appear to aliens. But more importantly, they seem “simplex” in their being stuck on what is being called multiplexity and having difficulty understanding what is being termed simplexity. They can only see things from a lot of points of view but not see the value of a fixed point of view… I think. Or something like that. Anyway, in Figments, they eventually discover that the human way of thinking is really complementary to their own, not just something horribly wrong.

In case it’s not clear, what’s so weird about this is that everywhere else it seems that multiplexity is superior to simplexity, and that multiplexity means not being limited. This seems to apply even in what Stewart and Cohen say otherwise. But here, they are complementary and each is limited without the other. Further, it seems they are themselves the kind of paradigms that simplexity can’t see beyond and multiplexity can. It’s like there are two levels plexity: The normal level, on which humans and Zarathustrans are just different. And a meta-level, which concerns being simplex or not between different levels of plexity; so the Zarathustrans’ normal state would be to be meta-simplex, just like we are, because they can’t understand how multiplexity and simplexity fit together.

I don’t really know what Stewart and Cohen were thinking of here, but I’d be remiss not to mention this angle as well. Anyway… if nothing else, it demonstrates how there are multiple ways of interpreting just what simplexity and multiplexity are. (How complexity fits into this view of the picture is another question I have no answer for.) It does seem a fairly valid point that if you look at things too much without a particular point of view, you might miss something too.

When we think of multiplexity (or complexity) as something better and desirable, it must imply that it’s something that understands simplexity too. This seems to describe Delany’s characters who explain Comet Jo these things.

The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld, by Terry Pratchett, Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen. Ebury Press, 2000.

(You can read “extelligence” as “culture” — that’s not completely accurate, but it’s close enough to understand this passage. The passage is about how it is turning from parochial — simplex — into, well, the internet age, or multiplex.)

Human extelligence is currently going through a period of massive expansion. Much more is becoming possible. Your interface to extelligence used to be very predictable: your parents, teachers, relatives, friends, village, tribe. That allowed clusters of particular kinds of subculture to flourish, to some extent independently of the other subcultures, because you never got to hear about the others. Their world view was always filtered before it got to you. In Whit, Iain Banks describes a strange Scottish religious sect, and children who grow up in this sect. Even though some members of the sect are interacting with the outside world, the only important influences on them are what’s going on within the sect. Even by the end of the the character who has gone into the outside world and interacted with it in all sorts of ways has one idea in mind and one only — to become the leader of the sect and to continue propagating the sect’s views. This behaviour is typical of human clusters — until extelligence intervenes.

Today’s extelligence doesn’t have a single world view, like a sect does. It doesn’t really have a world view at all. Extelligence is becoming ‘multiplex’, a concept introduced by the science-fiction writer Samuel R. Delany in the novel Empire Star. Simplex minds have single-world view and know exactly what everyone ought to do. Complex minds recognize the existence of different world views. Multiplex minds wonder how useful a specific world view actually is in a world of conflicting paradigms, but find a way to operate despite that.

Anyone who wants to can get in the Internet and construct a webpage about UFOs, telling everybody who accesses that page that UFOs exist — they’re out there in space, they come down to Earth, they abduct people, they steal their babies … They do all these things and it’s absolutely definite, because it’s on the web.

[…]

On the other hand, you can access another page on the Internet and get a completely different view. On the Internet, the full diversity of views is, or at least can be represented. It is quite democratic; the views of the stupid and credulous carry as much weight as the views of those who can read without moving their lips. If you think that the Holocaust didn’t actually happen, and you can shout loud enough, and you can design a good web page, then you can be in there slugging it out with other people who believe that recorded history should have some kind of connection with reality.

We are having to cope with multiplexity. We’re grappling with the problem right now: it’s why global politics has suddenly become a lot more complicated than it used to be. Answers are in short supply, but one thing seems clear: rigid cultural fundamentalism isn’t going to get us anywhere.

Less Wrong: “Introducing Simplexity”

About the only place I could find online where someone really discussed these concepts was here: http://lesswrong.com/lw/e7f/introducing_simplexity/

I’ll quote a lot of it here, but you can go to the original source to read the whole thing.

All three images, therefore, represent different types of fatally flawed thinking that have been directly addressed in past sequences. But this isn’t quite precise, so let me reveal the remainder of the answer as well: These three fallacies can all be said to consist of a very similar pattern of narrow thinking, false fundamental assumptions, and privileged hypotheses.

And this pattern seems so pervasive (in a large multitude of other fallacies as well) that it probably deserves a name of its own.

In Samuel R. Delany’s novella Empire Star, three terms (simplex, complex, and multiplex) are used throughout the novel to label different minds and different ways of thought. Although never explicitly defined, the reader understands their gist to be roughly as follows:

- simplex: Able to look at things only from a single, limited perspective.

- complex: Able to perceive and comprehend multiple ways of examining things and situations.

- multiplex: Able to integrate these multiple perspectives into a new and fuller understanding of the whole.

I will now appropriate the first of these terms to name the above mentioned pattern of biases. It might not be exactly how the author intended it (or then again it might be), but it’s close enough for our purposes:

Simplexity: The erroneous mapping of a territory that occurs due to the treatment of a complex element or a highly specific position or area in configuration space as simpler, more fundamental, or more widely applicable than it actually is.

But because it’s itself rather simplex to think that a single definition would best clarify the meaning for all readers, I’d like to offer a second definition as well.

Simplexity: The assumption of too high a probability of correlation between the characteristics of familiar and unfamiliar elements of the same set.

And here’s a third one:

Simplexity: Treating intuitive notions of simplicity as if referring to the same thing measured by Kolmogorov complexity or used in Solomonoff induction.

These all effectively amount to the same bias, the same flawed way of thinking.

Book Riot: “Simplex, Complex, Multiplex: Samuel R. Delany and Experience vs. Reading” (James Wallace Harris)

A little discussion about simplex–complex–multiplex in the context of literature and of experiencing new things.

Delany dealt with three reoccurring themes: naïve characters thrown into a complex world, characters being complexly confused by matching their experiences with others, and characters who are amazed by meeting wiser characters who apparently know the impossible. Delany called these mindsets simplex, complex, and multiplex (think multidimensionally complex). Connell and I have applied Delany’s insight from Empire Star in countless ways over the last half-century.

I can’t even explain this deep insight with so few words. You will need to read Empire Star. However, I do believe Delany’s observation of three mindsets and how they work can be applied anywhere without knowing how he specifically learned them. For example, once you get the hang of what he’s talking about, it makes understanding our bizarre politically polarized world easier.

In our argument, Connell asserts that travel is one of the primo methods for promoting multiplex thinking. This is exactly what Delany did in his stories. It’s also what Joseph Campbell describes The Hero With a Thousand Faces. What I tried to argue back that Connell didn’t believe, is reading can do this too. Connell said this was me rationalizing my self-consciousness over the lack of foreign travel. And that’s true, but it’s also true most of what we know about reality comes from reading.

Whether it’s from living or reading we all encounter new experiences going through the mental stages of simplex, complex and multiplex insights. A great writer can take us through them just like real world experiences can. Sure the gold standard of experience is real life. And for many people, real life and travel stay at the simplex level anyway. Complexity and multiplexity come from analyzing and abstracting our real world experiences.

No one today can travel to first century Rome. We will never know what it feels like to live in a city in the past. Yet, it’s my claim that reading a few books can tell us more about life then than most of its inhabitants ever knew while living.

Again, it’s abstractions versus feelings. But here’s the thing about being human, we only feel in the moment, in the eternal now, everything we remember feeling is an abstraction. And books can code that. But Connell’s argument included the fact that travel changes us. To make my rebuttal requires books being able to change us. Do they? How often have you said, or heard someone say, a book changed their life? I think they do. I won’t know what Connell thinks until he reads this essay.

Thinking in Systems by Donella H. Meadows

I have reviewed this book here. It makes no reference to Delany, but I thought the following quote is a fine description of a possible interpretation of multiplexity.

There is yet one leverage point that is even higher than changing a paradigm. That is to keep oneself unattached in the area of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that no paradigm is “true,” that every one, including the one that sweetly shapes your own worldview, is a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension. It is to “get” at a gut level the paradigm that there are paradigms, and to see that that itself is a paradigm, and to regard that whole realization as devastatingly funny. It is to let go into not-knowing, into what the Buddhists call enlightenment.

People who cling to paradigms (which means just about all of us) take one look at the spacious possibility that everything they think is guaranteed to be nonsense and pedal rapidly into the opposite direction. Surely there is no power, no control, no understanding, not even a reason for being, much less acting, embodied in the notion that there is no certainty in any worldview. But in fact, everyone who has managed to entertain that idea, for a moment or for a lifetime, has found it to be the basis for radical empowerment. If no paradigm is right, you can choose whatever one will help you achieve your purpose. If you have no idea how to get a purpose, you can listen to the universe.

It is in this space of mastery over paradigms that people throw off addictions, live in constant joy, bring down empires, get locked up or burned at the stake or crucified or shot, and have impacts that last for millennia.

[pp. 164–165]

I do recommend reading the book to get to know more of what this is about. And remember there’s my review for what the book is about in general. It’s a bit different than you might think from this quote.

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal: “Clouds 2”

This is from the often philosophical webcomic Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, here. One thing the comic has done repeatedly is mock the constant insecure insistence of human beings that we are superior. Here, a human tries to use the common “only humans are creative” line when talking to an artificial superintelligence that appears to be multiplex, or at least can touch that at the limits of its capacity.

Human: I guess when you look up there, you don’t imagine anything. You just see clouds.

Robot: Oh no. Of course, I do see clouds. I see the motion of suspended water and ice crystals. But I also see the cloud as a part of a vast climactic system — a thin sphere of clouds and whirls, gaps in the sky that open, close, that rend the ground with violence, that water the thinnest of orchids. At the same time, I see that water is intermolecular forces and ionic bonds, a dance of uncountable points on the shell of a blue sphere hung under a far off star. And the atoms of water themselves aren’t particular, but infinite ripples borne on invisible fields, stretching beyond human sight, journeying wherever the great first motion told them to go. And if I use every bit of my processing power, classical and quantum, I can see it all as a palimpsest of beauties, each bearing you along to the truth, until you find you’ve arrived back at the beginning.”

Human: Ah.

Robot: And what do you see?

Human: A turtle with, like, two heads.

Robot: And good for you, buddy!

[…] Simplex, complex, multiplex: A collection of quotes: Last I checked, the best resource on the Internet on this obscure topic from Samuel R. Delany’s works. I should update it soon with another quote that’s not easy to come by that I found… […]